An Article From the Archives:

With lean manufacturing, how much difference can a handful of people make, armed with know-how, some adhesive tape, a laminating machine, and rolls of Velcro? To hear the Visual Factory coordinating team at $600-million-in-sales Titleist Foot-Joy Worldwide tell it, if you’re looking for better flow, shorter cycle time, easier work, and fewer mistakes and accidents, that combination can make a very big difference. A few years ago, when a few stalwarts who’d been exposed to visual workplace training started to tidy the place up by putting strips of tape on the floor and signs on equipment, people laughed. But no more. In this month’s article taken from Productivity’s Total Employee Involvement Newsletter, April 1997, we learn how Titleist Foot-Joy Worldwide used visual workplace to make work easier.

The Fairhaven, MA-based golfing equipment manufacturer, for whom golf balls are the main staple, was much smaller back then and made only five models of ball. Today, 1500 associates at their four golf ball operations (all located in southeastern Massachusetts) churn out about a million balls a day, with 10 models, and about 300 inventory items. Their newest area, custom ball manufacturing, is also the fastest growing, going at about 15% a year. And people have stopped laughing about the visual factory: it’s making their lives better.

Says continuous improvement manager Jack Green, “From the very beginning, visual factory has been a good idea. But today, without it, we couldn’t keep things straight around here.” Adds team member Eileen Fernandez from the new packaging center, “It helps with lead time. If signs are hung where material is located, it’s easier to find it, and people get things out faster.”

Diane Latulippe, a pad printer in custom operations agrees: “We have big white totes full of every single ball type. Our setup people who get all the material for the pad printer used to have to go to the totes and sift through all of them to find what they were looking for. Now we have a sign hanging above each tote. It’s common sense and it makes things easier.”

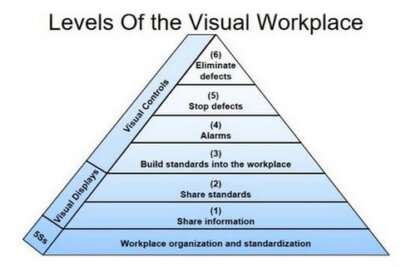

It’s about information, empowerment, and elimination of waste. The company’s management had been pursuing an enlightened employee empowerment strategy for some time. But empowerment without information only gets you so far. And the kind of information you need to get your job done in manufacturing operations is often about questions like: Where’s that part? How does this machine get set up? Where does this piece of equipment go? How much of what product is needed where and when, and where do I find it?

Says continuous improvement team leader Mike McDermott, “We’re looking to mistakeproof the operation as we go. By keeping things straight, there is a lot less clutter, people know where things are going, and there’s much better flow. We have fewer rejects, less rework. Moving into the visual factory has also helped us reduce accidents.”

A PLACE FOR EVERYTHING, EVERYTHING IN ITS PLACE

The goal of the visual workplace can be summed up in a single dictum you hear frequently in Japanese factories: a place for everything, and everything in its place. Writes Michel Greif, in the book The Visual Factory, “If a workplace is dirty or chaotic, the environment transmits incomprehensible messages. Why have finished parts been placed in an area for parts that are not ready? Why are tools not returned to their locations after repairs? Why does a container lack an approval label? Like the static in a poor telephone connection, disorder interferes with every level of visual communication.”

From day one, the Titleist team, with Green and McDermott in the lead as certified visual workplace trainers, has been making its way through the place organizing, standardizing, training, and communicating. Latulippe cites one telling example: “We use machine tools that all have the same size handles, but the heads have slightly different dimensions. You can’t easily tell which is which just by picking them up because they’re very close in size. So, we color-coded the handles and put a chart on each associate’s table letting them know what each tool actually turns, what the millimeter is, and how tb match it up. This eliminates damaging the machines or stripping the screws. It also helps with training.”

Information stations, called “doc docks,” now provide associates with all the documentation pertaining to their job right at their workstations. Says pad print associate Brian Fornier, of another innovation, “By labeling the setting on a control panel, as well as the machine itself, it is easy to recognize any abnormalities.”

The team learns as it goes. Whether it’s learning to scan color-coded images of specific golf balls onto the travel tickets that accompany product through the plant, creating a hand-cut, mistake-proof training template that fits over the knobs on a machine, or simply labeling with arrows a machine from Switzerland whose knobs move in an opposite direction to those standard in this country, team members demonstrate remarkable ingenuity in scanning the workplace for improvement opportunities.

The power of what they have learned was demonstrated recently at the opening of the packaging center in November, with production starting while construction was still going on. Since they only needed about 30% of the space at startup, people placed machines and material randomly. Says McDermott, “There was plenty of room, so people thought it didn’t make any difference where they put things. But as production went up and more equipment came in, we found we couldn’t keep track of things. The visual factory team went out and labeled everything: the equipment, the cabinets, what was in the cabinets. We put lines on the floor indicating where equipment should go: if you had a machine that would run a dozen totes, you knew it because its footprint was on the floor. Now when they take a piece of equipment out, it matches up. We’ve saved both setup time and time wasted looking for things.”

They learned one very practical lesson early. Before visual factory implementation, it was common for some ball presses to have labels glued on; when ball types changed, the labels didn’t, leading to confusion. In the beginning, the team taped changed visuals to the machines. Says Fornier, “It got to the point where we kept switching tape, which looked awful. The team brainstormed about what to do. We considered magnets, but a lot of the equipment doesn’t mix with magnets. That’s when we hit on using Velcro as an adhesive: it works, it’s neat, it’s cheap, and it takes less time to handle than tape.”

A TEAM OF INTERNAL CONSULTANTS

Each plant in the four-plant cluster has its own visual factory team that functions as a group of internal consultants, making themselves available to help anyone solve a problem using visual factory techniques. They meet regularly, without extra pay, as an add-on to other full-time responsibilities. Green and plant facilitator Lori Santos have begun to use Information Mapping™ to track and document manufacturing procedures step-by-step. They employ visual factory techniques in the documentation to make it easy for associates to follow.

Says Latulippe, “It’s actually the people on the floor who ask us into an area to help straighten things out. They might have an idea that they’d like us to implement. Once a person sees that it’s working in another area, he or she might say, ‘My job is difficult because of this and that. Could you try to come up with a solution?’ It just keeps going like that.”

And once they’ve got an area shipshape, how do they handle the chronically messy types who refuse to get with the program? Team member Roberta Rousseau says they are sometimes asked to go in and clean up after the messy ones: “It’s okay because at least they are involved.” Fornier sees it a bit differently: “After the third or fourth time, even the messy people start to come around: they start to think, ‘That’s where the pens go, that’s where the staples go.’”

Adds Fornier, “There are people who are initially negative about visual workplace. If you go out and put lines on the floor and put up signs, it doesn’t affect them. It looks good, but they’re not into it. But I’ve noticed that when you can show someone that it makes their job easier, as we have with training tools and laminated cards showing how to do setups, even the negative ones start to get involved.” Green agrees: “Once you start to do some of these things, it triggers more ideas for how you can visualize things, make them cleaner, or mistake-proof them.”

CREATING TEAM OF TEAMS TO STANDARDIZE

One recent development grew out of putting together a presentation for a conference last year. Up till then, each plant had its own visual factory team, with little inter-plant coordination. As a result of getting together to do their presentation, the plant teams decided to create an additional centralized team, with reps from each plant team, to share ideas and standardize new practices across all facilities. They meet every two weeks for an hour and a half to act as a visual information clearinghouse and to learn. Says Latulippe: “Sometimes ideas don’t work, sometimes they do. What the team is about is seeing what’s going on in the plants and learning from that.”

The visual factory teams also maintain “What’s New” boards near the entrance to each site that contain continuously updated information relevant to associates. Says Santos, “Whenever there’s a change made to our manuals, the way we do a process, we put in a change notice. We need to get every associate aware that we’ve made the change and the ‘What’s New’ boards give us a way to do this: everyone gets the information at the same time.

Believe me, whenever you go into a room and start writing something on the boards, people gather to see what it is!” In case someone is absent, they leave change information up for ten days.

LESSONS LEARNED

Team members, whose only reward for their involvement is the satisfaction of making change, clearly believe in the power of what they’re doing. It’s easy to see why: McDermott cites one dramatic example from an AlliedSignal facility they visited where one department doubled its productivity just by moving two pieces of equipment! So if they were starting over, what would they do differently?

Jack Green says he would try to build management awareness much sooner. “We did our conference presentation for a group of senior managers and they saw things they never knew before.” He’d get the multi-plant team going sooner, to get a richer mix of ideas and to begin the standardization process earlier.

Team member George Alexandre would see that all team members got computer training in things like Microsoft PowerPoint: “We tend to rely on one or two people to make all the pictures and graphs. Most of us don’t know how to produce them.”

Brian Fornier would be careful to involve people early who will be affected by a proposed change: “We moved a desk, for example, and the next day it was moved back. It looked good to us on paper, but it didn’t work for the operators. Now we work with them up front and we don’t get that kind of resistance.”

For his part, Mike McDermott says it’s very important to remember that it can’t ultimately be done by a small team: “We started small, in an isolated area, and rippled out. I’ve been here 25 years. During that time, we’ve tried a lot of things that last awhile then disappear. This is the first thing I’ve seen that keeps mushrooming. This makes sense: it makes things easier.”